By Ivanna Rodríguez-Rojas

Some cities cannot be synopsized, yet Miami in the 1980’s could be reduced to a caricature of three C’s, an unholy trinity of sorts — cocaine, crime, and Cubans. Conversely, for Cubans, the chosen triad of C’s would present themselves as cafecito, communism, and COÑOOOO! Beyond contentious realities of the socio-economic, cultural and political landscapes of the 1980’s, this infamous decade is distinguished by the mass exodus of Cubans to the Floridian peninsula via Mariel boatlift. The systemic exile deemed the emigrants as escorias de la sociedad — ‘scum of society,’ resulting in a misconstrued public perception of the newcomers. Enter Radical Conventions, a landmark exhibition for Cuban American history— a purposeful deviation from the complacency of a historically identity-focused narrative, and locating Cuban American artistic expression against broader contexts manifested through various aesthetic conventions of the era.

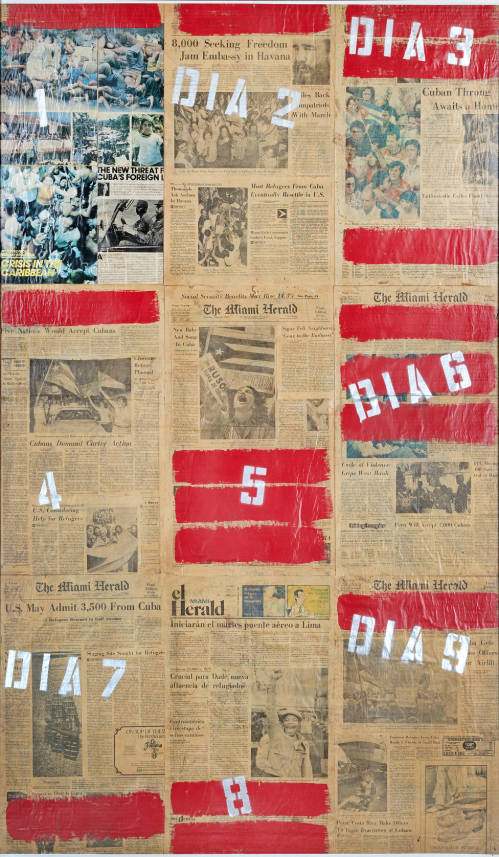

Detail View of Fernando Garcia, 10,865, 1980. Courtesy the Lowe Museum of Art.

A self proclaimed counter-narrative exhibit at the Lowe Museum, Radical Conventions displays the works of over 25 Cuban American artists in the 1980’s. It’s not a survey, but rather, a testament to the versatility within the interdisciplinary interpretations brought forth by Cuban artists, which address the complexities of Cuban American identity. Though the exhibit’s nearly 100 works align with standards of contemporary art, the radicality of the corpus produced by the artists on display is informed by culturally specific engagements with their chosen visual language. With that, curator Elizabeth Cerejido challenges and explores the nature of Cuban diasporic art, which subsequently highlights the impact of other identities beyond biculturalism and U.S-Cuba relations by positioning the works on view in conversation with issues related to sexuality, gender, religion, class, and political stances.

Amongst the selection of works, it was expected to see Ana Mendieta’s work. The concept of the abject body, so innate to Mendieta’s oeuvre, represents not only her particular navigation of identity, but mirrors the tumultuous realities of Cubanidad. In particular, Esculturas Rupestres, or Rupestrian Sculptures (1981), accomplishes a tangible sense of permanence which boldly contrasts the ephemerality of previous works where her body is utilized as the primary medium. The earth carvings, produced during her visits to Jaruco, Cuba, are a continuation and conclusive statement to the series of earth-body sculptures she commenced in the mid 1970’s. Titled after Taíno goddesses––Cuba’s indigenous population who were exterminated by Spanish colonizers, each carving intentionally places the female figure in a historically and symbolically rich environment. Esculturas Rupestres inhabits cave formations known as the Jaruco stairs, which served as a hiding place for runaway slaves as well as for mambis, the rebel army who fought for Cuban independence in the late 19th century. For Mendieta, the process of creating the carvings in such space, going as far as seeking permission from the Cuban Ministry of Culture, contributes to the radicality of her work.

Still from Tony Labat, Kikiriki, 1983; video (color, sound), 11 minutes and 57 seconds. Courtesy the Lowe Museum of Art

Another standout piece, Kikiriki (1983), furthers the identifications of Cubanidad into filmic narratives. Tony Labat’s video installation features a cacophony of visual and auditory symphonies––conversing with each other yet jarringly dissonant, stuck in an endless loop. The retro television sets project a feverish collection of clips filmed on the Cuban island, figments of news broadcasts, interviews, and more notably, scenes of the ocean––which bring forth the all too familiar element of in-betweenness for Cubans on and off the island. Similarly, Félix Gonzáles-Torres’ Untitled (1987), effectively conveys Cuba’s complicated relationship to the ocean by literally turning an image of it to a jigsaw puzzle. By this manner, both artists achieve a representation of the Caribbean Sea as the ultimate borderland, becoming not only the physical frontier, separating oppression from liberation, but simultaneously acting as an oppressive and freeing entity itself. Even the more thematically blatant ‘Cuban American’ pieces like Fernando Garcia’s 10,865 (1980)––pushes standards by embedding mathematical dialogues within the immense Granma newspaper collage, an otherwise ‘traditional’ convention of Cuban American identity. Radical Conventions is revolutionary within its kind, especially for a Miami exhibit. Its marvelous displays of reflections and experiences cleanses our palate from the absurdity of the accepted discourse surrounding the island. It is a righteous, and loving homage to the multifacetedness of Cubanidad, the 1980’s, and the immortality of those who lived and continue to live through them.

Ivanna Rodríguez-Rojas

Ivanna Rodríguez-Rojas is a Montreal-born, proud Miami-raised, Cuban-Mexican artist, plant mom, and educator based in Harlem. She received her BA in Art History and Anthropology from Barnard College and has interned at the Perez Art Museum Miami, The Bass Museum, the Guggenheim, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Immigrating twice by the age of seven – she centers her work around displacement/rootedness, childhood, reimagining borderland identities; and coined the term ‘Nepantla Art’ (informed by Gloria Anzaldúa’s research): a Nahuatl word for in-betweeness, with the goal of ascribing actuality to the experience of wholeness and fragmentation via artistic expression. She now teaches a class of fantastic first graders full-time but continues to develop her writing and photography.