By Jason Katz

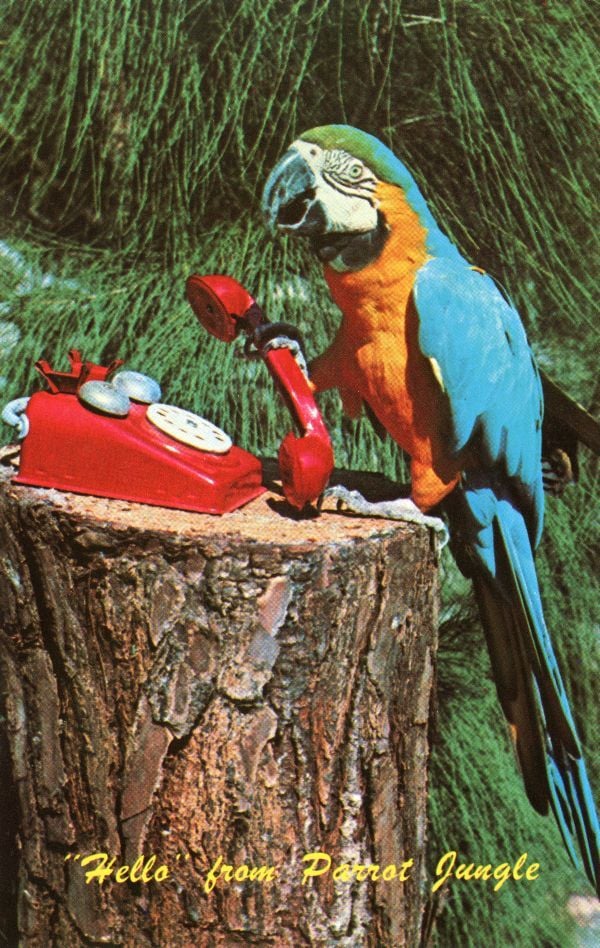

Parrots rule the Miami imaginary. Anybody who’s been here since the 90s (or before) will remember the Parrot Jungle. Founded in 1936 by Austrian farmer Franz Scherr and his wife Louise, it was one of Miami’s most famous roadside attractions. Having worked with proprietors of other roadside attractions like the Monkey Jungle, Scherr saw that people gravitated towards those exotics which were harmless. He acquired a hardwood hammock which had previously served as the home to a nudist colony, and transformed it into a tropical paradise. In his book, Miami’s Parrot Jungle and Gardens: The Colorful History of an Uncommon Attraction, Cory H. Gittner writes, “Like a postcard that has come alive, the Parrot Jungle is permanently perched beside the orange, the alligator, and the bathing beauty as the exotic ideal of a Florida vacation.” At Parrot Jungle, folks could have their photos taken with macaws and cockatiels, proving to their friends that they had fun in the sun. The birds were sometimes caged but often allowed to come and go as they pleased. Many came back. Eating was good at this manufactured Parrotopia, after all. When it closed in 2002, many of the parrots scattered throughout the city. Their presence is almost always welcome to this writer.

My writing practice is Parrotological. When I’m stuck, I step out onto my Coral Gables sidewalk and stroll around until I hear the squawk of macaws. The din of the smaller green ones is easily distinguishable from their larger blue and gold counterparts. These macaws sound prehistoric. They’re not only a relic of archaeological time but of recent roadside history too. The opportunity to reflect on history is crucial during this great acceleration.

The blue and golds usually travel in pairs. They roost in the crevasses of the newly built fire station nearby. It’s ust one of the structures they’ve co-opted for themselves throughout town. The parrots of Miami–hyacinth macaws, mitred parakeets, red shouldered macaws, etc.–are what are known as synanthropic creatures. Though they are classified as non-native exotics, synanthropic means they thrive thanks to their relationship to the built world. High rises offer habitats similar to their South American cliff dwellings. They munch on nearly every kind of subtropical tree, from sea grapes to foxtail palms. My constitutionals reward me with inspiration – the knowledge that at least somebody’s thriving here.

Hello from Parrot Jungle, Red Road, Miami, Fla. 1936 (circa). State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

In his book Miamificiation, philosopher Arman Avanessian writes in second person of the way his body adjusted to living in the Magic City. “You get excited about the idea of a Miami mimesis,” he says. “You prophesy a miamisis for your writing (get up early, write, go swimming, when it gets too hot on the beach, another writing session in the afternoon before the long evenings and nights begin).” I abide by a sort of Parrotisis. My moods and rhythms are influenced by the cries of my colorful sky lords.

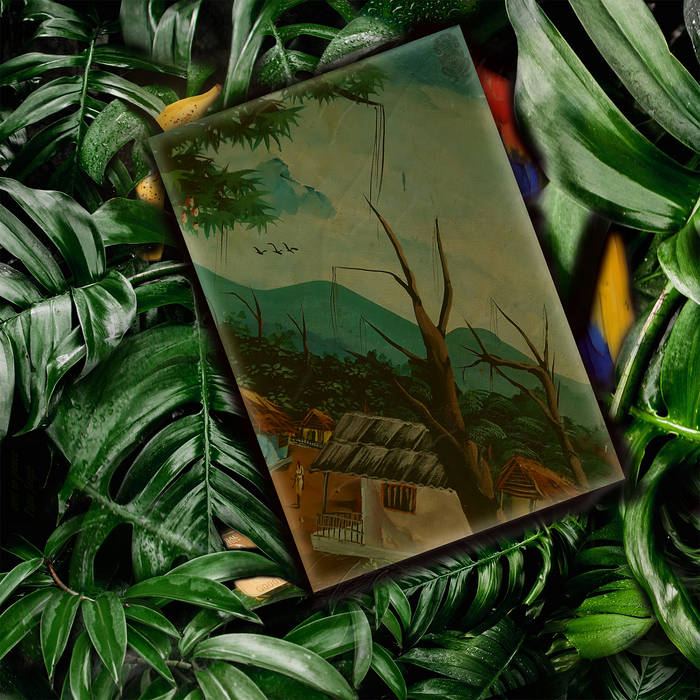

I am not alone. Parrots pervade local art. Take musician and artist Nicholas G. Padilla’s 2020 album, Parrot Jungle. The title is directly derived from the former roadside attraction. The artwork for the album is of a cassette case nestled in a jungle of tropical flora including monstera and palm leaves. There are hidden symbols photoshopped in, like a bar of gold, a banana, and a scarlet macaw. The cassette itself is styled as a watercolor depicting a Caribbean village: there are clay streets, mountain ranges, a woman sweeping the street, and colonial balconies. The album is a sonic trip which pits Padilla’s identity–a lineage traced back through Venezuelan, Puerto Rican, and Cuban indigeneity–against drum and bass, merengue, and vaporwave beats. The song titles, including “Macando Wars” and “Agro-Industrialization” refer to the damage wrought onto indigenous peoples of Latin America by imperialist interests. The album juxtaposes the nostalgia of youth with a loss of identity. This is the microcosm of Miami living. The duality of beauty and destruction – the specter of the parrot. “For me, the parrot symbolizes the spirit of the tropical jungle,” he tells me. “I picked the name for this album, which also happened to be my former alias, for its hauntological qualities. When I first saw the parrots in the dome at Parrot Jungle, my life changed. I didn’t know it then but I was reconnecting to my ancestral past through a controlled and contained environment.” In Venezuela, Padilla’s grandparents received parrots in lieu of payment for services they rendered unto the community. Bartering was common where they were from. His grandmother had a collection of scarlet macaws.

Album Cover of Parrot Jungle by Nicholas G. Padilla. 2020.

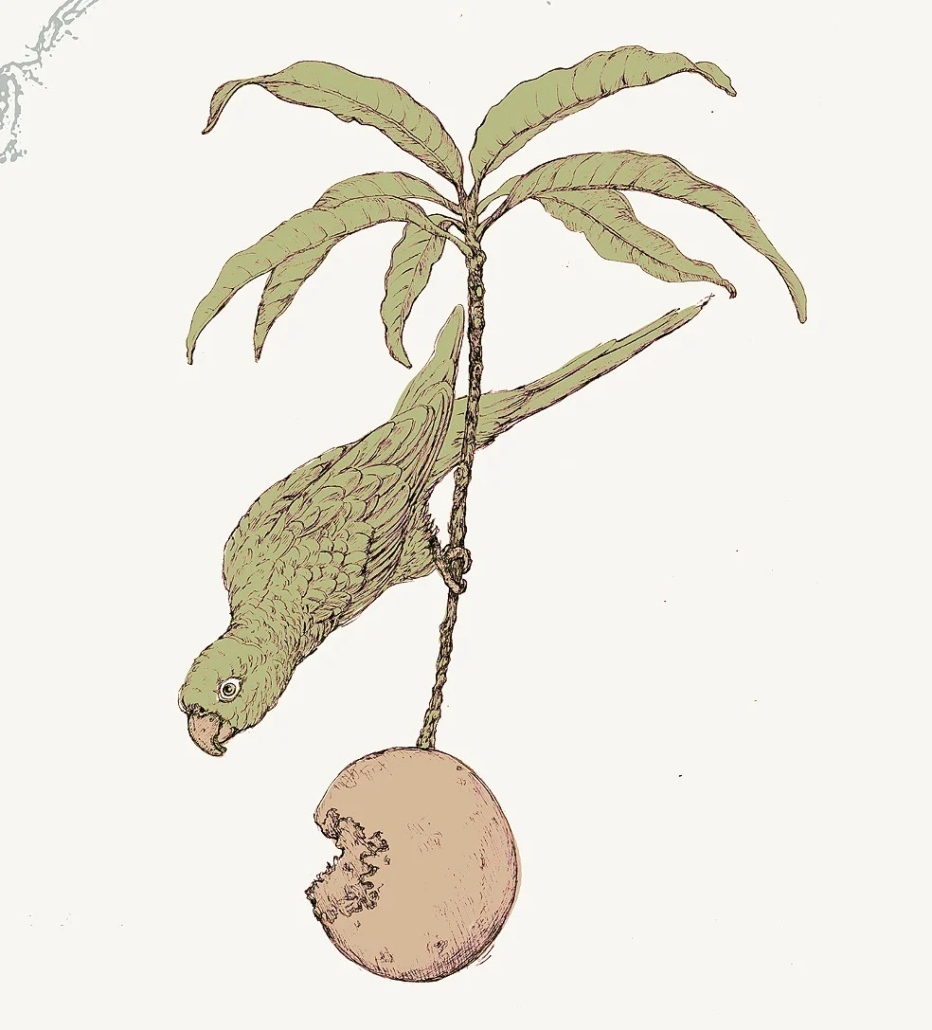

Then there was Parrots in the Kiln, a 2022 group exhibit in Miami’s Design District. The name of the show is a play on the title of Chicano writer Victor Martinez’s 1996 novel El Loro en el Horno. The book’s name comes from a folktale about a parrot who is complaining about how hot it is in the shade without realizing he is actually inside of an oven. The artists–Beatriz Chacamovitz, Lauren Shapiro, and Morel Doucet–work with ceramics (hence the “kiln” pun) and their works all address South Florida’s ecosystems and their vulnerability to climate change (ignorance to imminent doom.) They use the image of a parrot as a way into art about the environment. Besides appearing in the title of the show, parrots are in the background of the works presented, literally. Artist Christina Pettersson’s The Forgotten Frontier, an installed wallpaper which serves as an archival reference to South Florida’s history of destruction and reconstruction, includes metaphorical, almost even implied ouroboros images of parrots nibbling on oranges. Pettersson incorporated even more parrots into a recent public mural for a project called the Caribbean Village.

Closeup view of Caribbean Village Mural by Christina Pettersson. Courtesy of the artist.

Closeup View of The Forgotten Frontier by Christina Pettersson. Courtesy of the Artist.

For Pettersson, parrots have been an inspiration going way back. “Some of my most formative memories from growing up here weren’t from my family’s golf-course fronting home in Hialeah but rather my grandmother’s place across street from the Parrot Jungle,” she tells me. “The parrots would fly over to her house and eat from the trees.” She remembers a time not so long ago when that neighborhood was full of cow pasture and horse barns. Pettersson’s nostalgia for youth and exotic South Florida mirrors anybody’s experience in a place where the only constant is change.

In 2015, Pettersson decided to pay homage to one specific parrot of her youth. “There was one bird in particular named Tina, a pretty white cockatiel, who rode a tiny bicycle across the highwire. As soon as I saw her I was hooked,” she says. Pettersson invited Amanda Sanfilippo to serenade some parrots at the former location of Parrot Jungle. By then it’d become a community park, garden, and event space. After years of performing for us, and inspiring us, Pettersson wanted to give them a song. Inevitably, their instincts kicked in though and they started dancing for the crowd.

For many of us here today, parrots are the way into ideas but for many in the past, parrots were a way into Florida itself. “In reality,” Gittner writes, “Parrot Jungle was only miles from a metropolitan area, but to its visitors it was a misty, faraway place—a green-draped fantasy of gurgling pools, slithering reptiles, twisting vines, scented flowers, and squawking birds of impossible brilliance flashing in the tropical sunlight.” When it came to the colonization of Florida, it was always exoticized first and then developed shortly thereafter. In today’s context, Miami’s aesthetic beauty is a draw to a few who’ve made it unaffordable to the many. Sometimes, looking to the sky with a leery eye, I wonder who else is inspired by the parrots – maybe to post them on social media or to name a condo project after them? The roadside attraction itself is mostly dead but the entire city has become a Parrot Jungle.

Jason Katz

Jason Katz is the Contributing Editor for Miami. Miami-born and raised writer and educator, Katz publishes Islandia Journal, a printed literary magazine of (sub)tropical myth, folklore, cryptozoology and the paranormal. His work has been featured in the Miami New Times, Bitter Southerner, Saw Palm, Miami Magazine, Miami Rail, and the Seminole Tribune.